NEW YORK (CNNMoney) For the vast majority of small business owners, the hotly debated Hobby Lobby ruling will have no direct impact.

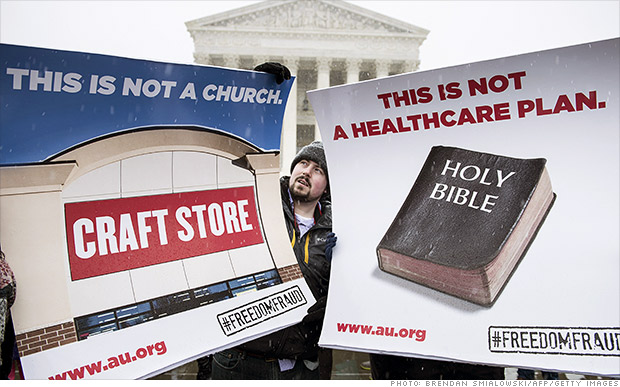

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) For the vast majority of small business owners, the hotly debated Hobby Lobby ruling will have no direct impact. On Monday, the Supreme Court ruled that "closely-held" for-profit corporations (those that are majority owned by five or fewer people) can be granted religious exemptions from certain contraceptive coverage (such as IUDs and the morning-after pill) required under the Affordable Care Act.

Hobby Lobby is by no means a small business -- it has nearly 600 stores and some 13,000 employees. But the Supreme Court's description of "closely held" companies calls into question how far the ruling might extend.

Seventy-eight percent of small businesses are family-owned, according to LIMRA, an insurance trade research firm -- but only 2% of small businesses have 50 or more employees. This is key to the Hobby Lobby decision because any business with fewer than fifty employees is already exempted from the health insurance mandate under the Affordable Healthcare Act.

Of that 2%, businesses would have to prove a "sincere" religious belief in order to be exempt. While it's unclear how the sincerity will be tested (or how many businesses might make this claim), it's unlikely to be in most companies' best interests to go that route.

The actual cost of the contraception to employers is relatively minimal. According to 2011 report from the Actuarial Research Corporation (which used data from 2010) the corporation's estimated annual cost, as part of an insurance plan, is $26 per enrolled female. This amount includes all contraception, like standard birth control pills, which was not disputed in the Hobby Lobby case.

"From a purely economic perspective, [unintended pregnancies are] going to cost me and my insurance provider a lot more than birth control costs," said Jim Houser, owner of Hawthorne Auto Clinic in Portland, Ore., and executive board member of the Main Street Alliance.

He employs eleven workers -- four of whom are women -- and provides them with complete coverage despite not being legally obligated to do so.

"But, that's not my decision to make," added Houser. "Businesses have absolutely no business being involved in the personal relationships of any employee -- especially with a woman and her doctor."

Houser isn't the only one questioning the Supreme Court's decision. Laurie Sobel, senior policy analyst with t! he Kaiser Family Foundation, said there are still a lot of questions that need to be answered by the Department of Health & Human Services: How will the new exemption be enforced? Will companies self-certify (as nonprofits do) or will there be some sort of test to determine the sincerity of a company's religious beliefs?

There are also serious concerns about what this might mean for businesses that object to other aspects of health coverage. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg raised many of them in her vehement opposition.

"Would the exemption...extend to employers with religiously grounded objections to blood transfusions (Jehovah's Witnesses); antidepressants (Scientologists); medications derived from pigs, including anesthesia, intravenous fluids, and pills coated with gelatin (certain Muslims, Jews, and Hindus); and vaccinations ?" she wrote.

"The court, I fear, has ventured into a minefield," Ginsberg added.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the contraceptive coverage allowed under religions exemptions.

No comments:

Post a Comment